The October 2024 Private Bird Tour with Saudi Birding

- saudibirding

- Oct 20, 2024

- 27 min read

Updated: Dec 23, 2025

Tour Dates: October 5 - 13, 2024

Guests: Jonathan Franzen and Charles Hood

Guide: Gregory Askew

Avian Highlights:

Sand Partridge

Arabian Partridge

Philby's Partridge

Lesser Flamingo

Rameron Pigeon

Dusky Turtle-Dove

African Collared-Dove

Red-eyed Dove

Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse

White-browed Coucal

Pied Cuckoo

Egyptian Nightjar

Nubian Nightjar

Montane Nightjar

Plain Nightjar

African Palm Swift

Red-knobbed Coot

Terek Sandpiper

Broad-billed Sandpiper

Crab-Plover

Black-winged Pratincole

Sooty Gull

White-eyed Gull

Saunders's Tern

White-cheeked Tern

Abdim's Stork

Great White Pelican

Pink-backed Pelican

Hamerkop

Goliath Heron

Oriental Honey-Buzzard

Booted Eagle

Steppe Eagle

Gabar Goshawk

Levant Sparrowhawk

Arabian Scops-Owl

Arabian Eagle-Owl

Pharaoh Eagle-Owl

Little Owl

Desert Owl

African Grey Hornbill

Grey-headed Kingfisher

Arabian Collared Kingfisher

Arabian Green Bee-eater

Abyssinian Roller

Arabian Woodpecker

Lesser Kestrel

Sooty Falcon

Black-crowned Tchagra (Arabian)

Asir Magpie

Greater Hoopoe-Lark

Bar-tailed Lark

Black-crowned Sparrow-Lark

Singing Bushlark

Rufous-capped Lark

Common Reed Warbler (Mangrove)

Brown Woodland Warbler

Scrub Warbler (inquieta and buryi)

Yemen Warbler

Arabian Warbler

Menetries's Warbler

Abyssinian White-eye

Arabian Babbler

Tristram's Starling

Yemen Thrush

Black Scrub-Robin

Little Rock-Thrush

African Stonechat

Buff-breasted Wheatear

Blackstart

White-crowned Wheatear

Arabian Wheatear

Nile Valley Sunbird

Palestine Sunbird

Shining Sunbird (Arabian)

African Silverbill

Arabian Waxbill

Spanish Sparrow

Arabian Golden Sparrow

Richard's Pipit

Arabian Grosbeak

Olive-rumped Serin

Yemen Serin

Yemen Linnet

Cinnamon-breasted Bunting

Other Wildlife Highlights:

Hamadryas Baboon

King Jird

Kuhl's Pipistrelle

Hawksbill Sea Turtle

Yemen Rock Agama

Anderson's Rock Agama

Arabian Tree Frog

Eurasian Marsh Frog

Asir Garra (endemic freshwater fish)

This month I had the honor and pleasure of personally guiding American novelist, essayist, and passionate birder, Jonathan Franzen, and his friend, nature writer and poet, Charles Hood, during their recent visit to the Kingdom. Our nine-day private tour took in the gravel-sand deserts and sandstone canyons of the Riyadh region, the wooded wadis, escarpments, and plateaus of the Al Bahah and Asir highlands, as well as the canyons, foothills, lowland farms, and coastal hotspots of the Jazan region. Ultimately, we had some excellent birding throughout and managed to find over two thirds of our targets, including all sixteen of the Arabian endemics and all but one of the near-endemics. Our final tally was an impressive 197 species. This was by far the best showing for any Saudi Birding tour, with several really standout encounters.

Day 1—Riyadh

An early start as usual in Riyadh got us out to Rawdat Nourah right at sunrise. We were meeting up with Mischa Keijmel, who has made the desert and hills around the rawdah one of his local patches. Our main target, of course, was the near-endemic Arabian Lark, which the June tour and I found with surprising ease given how extensive the habitat is here and how few Arabian Larks occur. This visit, however, the streaky brown lark with the honking pink beak was MIA. We couldn't rue over our failure for long, though, as Jon and Charles had several other targets for the day to keep us busy. To that end, our search for Arabian Lark turned up a couple of other lark species on the target list, with great views of Bar-tailed and Greater Hoopoe-Larks. The few kestrels we encountered here turned out to be Lesser, our visit proving to be a good time for their passage. There were migrants and winter residents on the target list as well. While it proved too late for some of the former and too early for some of the latter, we did get our first Menetries's Warblers of the tour here.

Next we headed to a series of sandstone wadis nearby for desert species that eschew the flat, open terrain of Rawdat Nourah. The escarpments, jebels, and wadis in this part of the Kingdom formerly composed the key topographic features of a prehistoric sea that once stretched across this region. Fossils of the marine creatures from that time can be found throughout. Just as once the shelter of these features attracted a rich diversity of sea life, so too today they attract an array of resident and migratory terrestrial species. At one of our stops we hit several of our targets in short order. Hearing a familiar call overhead, I soon had everyone on a flock of Trumpeter Finch on the opposite side of the wadi. Further up the wadi, we had a pair of Blackstart, flushed our first of two flocks of Sand Partridge, a locally common but shy denizen of arid mountains in Arabia, and found migrating Red-backed Shrike and another Menetries's Warbler. Then on our way back to the cars to head to our next wadi, sweet, high phrases of a wheatear's song caught my attention. Guessing either Hooded or White-crowned based on the habitat, we began scanning the wadi edge opposite us and soon picked up two adult White-crowned Wheatear, one of the handsomest birds of the Saudi deserts.

At our next spot, a place where Mischa had camped a week or so prior, we found surely the best bird of the day. During his overnight in the area, Mischa had recorded owls calling from two different locations. The next morning he went looking for them and discovered they were Pharaoh Eagle-Owls. Scanning one of those spots on our visit, we managed to relocate one of the owls sheltering just inside a cleft in a hillside. Our good fortune with owls would continue with this attractive Bubo the first of five owl species seen during the tour.

After stops in Huraymila and Solbukh, where we added more resident and migrant species to our trip list, including Arabian Green Bee-eater, Brown-necked Raven, Masked Shrike, Eastern Olivaceous Warbler, Scrub Warbler (ssp. inquieta), and Black Scrub-Robin, we headed to the airport for our afternoon flight to Al Bahah.

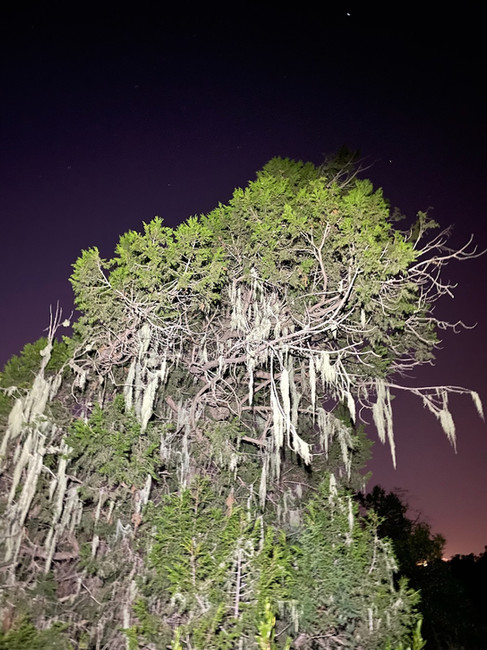

Day 2—Al Bahah

We spent our first morning in the southwest highlands with only one matter front of mind—finding Arabian Grosbeak. With stops planned in Tanomah, Abha, and Habala, I wasn't worried about our chances of seeing the other Arabian endemics, but having dipped on the grosbeak back in June, despite searching the better part of two days, had me laser-focused on finding one this visit. To that end, we staked out the best vantage points around the wooded wadi it's been frequenting since fall 2021. One spot became quite birdy just as the sun began penetrating into the wadi bottom, with several highland specialists, like Olive-rumped Serin and Yemen Linnet vocalizing around us. High up the opposite side of the wadi, somewhere on a more open, rocky slope, we heard our first Philby's Partridge and a short time later, just upslope from us in a scrubbier patch, our first Arabian Partridge. Below us, in the thicker vegetation dominated by dense juniper crowns, White-spectacled Bulbul, Abyssinian White-eye, Arabian Babbler, and Yemen Thrush were revving up for the morning's activity. Using a little playback at a familiar call from within deeper scrub produced our first Arabian Black-crowned Tchagra.

Before long I picked up distant snatches of grosbeak song from two places—one deep in a cluster of junipers opposite us and another far upslope to our backs. Scanning for the nearest bird, Jon caught his first glimpse of a likely grosbeak, which he then lost track of. More vigilant waiting ensued. Further down the wadi I caught sight of two grosbeaks in flight, but both had flown out of view before I could get Charles and Jon on one. All of my encounters with this species in Saudi have started this way, an agonizing prelude of teasing—a flash of gold here, a white cheek patch there, quiet singing deep inside a juniper—and only after patiently waiting and watching did we finally get clear and clinching views. So too this time—after probably 15 to 20 minutes of glimpses here and there around the wadi, I picked up on sustained singing upslope from us. Scanning with my bins, I finally found a male Arabian Grosbeak against the sky on the ridgeline above us. While distant, we all got decent scope views. The wait was over—tick!

Even better, during breakfast at a spot in the wadi bottom, further grosbeak song caught our attention and we looked up to find another male singing away atop a bare juniper spire directly across from us. We were totally gripped!

Getting the grosbeak early took the pressure off for the rest of the morning. I was confident we'd see all the other endemics at our other highland stops. Having heard partridges earlier though, I figured we'd try to find some in Al Bahah, the only area besides Tanomah where I had seen both species, so we headed to a wadi where I had seen Philby's the previous year. Driving slowly along the edge of the same open terrace field, we didn't see any partridges but a dark-backed bird with black-and-white barring in its wings rose up from a short acacia beside the track and flew off in the direction of a taller stand of trees. The undulating flight was an telltale giveaway—woodpecker!

A quick search of the trees revealed not one but two handsome male Arabian Woodpeckers, which perched in the same tree in perfect morning light long enough for Jon to get jaw-dropping views. These would prove to be the only woodpeckers we'd find during the tour—while not uncommon, they can be quite unobtrusive—so this encounter was another testament of our good fortune.

Making a wider search of this spot we hit a few more of our targets with Arabian Warbler, Wheatear, and Waxbill showing well. We also got close views of a freshly plumaged Southwest Arabian subspecies of Long-billed Pipit.

With some time left before lunch, we visited Wadi Al Ghaleel, a more remote wooded tract that I had never birded before. It was a little quieter that late in the morning, but we had some nice birds, including migrants new to our trip list. Here we had our only encounter with Gambaga Flycatcher, which is a common summer breeder but that clears out in the fall, possibly wintering in Yemen or East Africa. New to the list were Eurasian Blackcap, Common Redstart, and Ortolan Bunting.

After lunch we hit the road for Tanomah, aiming to arrive with time enough to check in to our hotel, grab some takeaway, and get to our owling spot right at sunset. This proved a great plan, proposed by Jon, whose input invariably resulted in better birding opportunities all around. We sat with our meals with a perfect view of an area where Arabian Eagle-Owl has been reliably seen over the past several years. Sure enough, with twilight still providing enough illumination for us to see the various ledges, crags, posts, and poles where the owls have been seen perched in the past, one flew into view and perched on a piece of PVC piping jutting from a wall. It stayed there long enough for me to set up the scope and us to enjoy great views, unassisted by flashlights.

Once the eagle-owl had flown off and we had finished our dinner, I led us over to an area close to some rocky peaks ringed by juniper stands I thought might be good for Montane Nightjar and Desert Owl. Using playback we were able to get a response from two Desert Owls but nothing from the nightjars. The owls, however, were disinclined to come any closer and despite thermaling and spotlighting the area from which the closest bird had been calling, it was too distant to locate. We had to resign ourselves with "heard only", effectively a non-tick for Jon, who only counts birds he's actually seen.

Last up was Arabian Scops-Owl. We had one bird responding to playback. Though close, it took a moment to pin down its location in a large acacia. Thermaling revealed the bird, and soon we had it spotlit and showing well for both Charles and Jon. Solid tick, that one!

Our work was done for the evening. Time for bed!

Day 3—Tanomah

We started the next morning at my partridge spot in Tanomah just before sunrise. Just as the sun began hitting the tops of the hills around us, we soon heard our quarry—Philby's Partridge—calling from the ridgeline opposite our stakeout spot. While scope views of this striking endemic aren't ideal, sometimes they're the best to hope for given how shy and flighty they can be.

Listening to a podcast earlier in the week on the founding of Saudi Arabia in the early 20th century, I learned a very unsavory detail about Harry St. John Philby, the British intelligence officer, renowned Arabist, and geographer, from whom the eponymous partridge got its name. Apparently, he kept a concubine (i.e. sex slave) that King Abdulaziz Al Saud, the first ruler of the modern state of Saudi Arabia, had gifted him for his good counsel. While slavery had long since been abolished in the Western world, slavery on the Arabian Peninsula had actually revved up in the early part of the 20th century and wouldn't be formally abolished in Saudi Arabia until the early 1970s. Needless to say, it was very much beyond the pale for a British subject, no matter his attitudes toward his home country, to have been exploiting an enslaved girl in the modern era. For this reason, perhaps we might consider a name change for the partridge that bears his, in keeping with similar efforts in North America.

After we left the partridges to their morning pursuits, it was time to search for the one species that can only be found in Saudi Arabia—the Asir Magpie. Driving through an area known for them, we eventually came up two birds flying off towards one of the villages. Tick! I soon had them in the scope and we watched as they moved from roof to roof in the village until dropping down into one of the nearby terrace fields. Further on, we came upon another magpie, got great views of our first Yemen Warblers and Buff-breasted Wheatear, saw two more Philby's Partridge, and got brilliant views of a Booted Eagle to boot!

Unfortunately, there have been no recent updates on efforts in the Kingdom to protect the Asir Magpie, despite its designation as critically endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Failure to prevent the extinction of Saudi's sole endemic bird species would be an unfortunate and lasting stain on an otherwise improving record for the protection and preservation of the Kingdom's natural heritage. Hopefully, renewed efforts on behalf of the magpie will be forthcoming and reverse what has been the precipitous decline of this iconic bird.

After breakfast, we headed to one of Tanomah's stunning national parks to see what other targets we might find. In particular, this spot has been good for Yemen Serin. We made a circuit of the area, focusing around the bases of boulder-strewn slopes, favored habitat of the serin. There were many nice birds about, including Graceful Prinia (ssp. yemenensis), Brown Woodland-Warbler, Scrub Warbler (ssp. buryi), more Yemen Warbler, Yemen Thrush, Yemen Linnet, and Olive-rumped Serin. Yet not the Serin we came for. That is, until I heard a faint but familiar call nearby. Waving Charles and Jon over to me, I whispered Yemen Serin and began trying to locate where the calls were coming from. Soon enough I found the quintessential LBJ tucked, uncharacteristically, inside a juniper tree. I put my scope on the bird as it preened contentedly in the tree, allowing Jon a close study of the plumage differences that distinguish Yemen from Olive-rumped.

Overhead that morning we picked up Little Swift, Eurasian Sparrowhawk, Fan-tailed Raven, and had a nice flight of Steppe Buzzards, the most common large raptor during the tour.

After checking out of our hotel in Tanomah, we hit the road for Abha, making a couple of stops along the way. Even though we'd seen Asir Magpie earlier, I always like to pay a visit to the family groups in the villages of the Bihan area. We heard a couple of magpies at our first stop, but it wasn't until our final stop here that we actually bumped into a few. The one closest to the road was occupied with something in a tree as we pulled up. We watched as it worked over an object of interest—looking like a cork at first but perhaps a shotgun shell—gripping it with its foot for leverage like a parrot. With every encounter with these intelligent birds a new opportunity to observe interesting behaviors.

At a subsequent stop, we found a small flock of Lesser Kestrel feeding on grasshoppers in a field just off the road. While we were scanning the kestrels, two more Asir Magpie flew past. This particular area marked nearly the southernmost edge of the magpie's range in the region as a few kilometers further on the highland junipers became shorter and shorter in height until eventually we reached a long, barren stretch that extends almost the remainder of the way to Abha. It's a combination of the magpie's short-range dispersals and the lack of suitable habitat along long stretches of the highlands that has contributed to its currently fragmented and highly restricted range.

After such a successful morning and having made good time to Abha, we had a big lunch at a Turkish restaurant and then took advantage of a chance for down time at the hotel before our next night birding session.

Arriving at the escarpment edge shortly before sunset, we hiked down the track where the June tour and I had found Montane Nightjar. We spent about an hour here thermaling ahead on the track and using playback here and there but couldn't locate any nightjars. It was a fairly chilly evening at 3000 meters ASL, which led me to believe that this resident nightjar had likely already retreated to lower elevations. We'd have another opportunity in the mountains of Jazan two days later that would prove successful.

Day 4—Abha

Early the next morning we were making our way down the steep escarpment road at Raidah Preserve looking for our second-to-last endemic target—Arabian Partridge. We'd heard Arabian in Al Bahah and in Bihan but hadn't yet seen any. Raidah has proven the most reliable place for them, particularly in the early morning when they can often be found feeding along the edge of the road. We got out in places along the way, the first of which produced a nice Rameron Pigeon. This would be the first of nine birds we'd ulimately encounter that morning. Also at this stop we found an African Stonechat, the first I'd seen at Raidah.

A little further on we found a beautiful Gray Wagtail and then a flock of Rameron Pigeon. It was with another few switchbacks that we eventually spotted a small covey of Arabian Partridge, just as they dropped out of sight over the edge of ravine. Jumping out of the car, Jon and I searched the spot where we had lost them and got good views as two birds flew across the ravine just below us. One more endemic to go and we will have seen the full suite of species that can only be found on the Arabian Peninsula.

As we neared the bottom of the escarpment, we found our first resident Afrotropicals in the form of Dusky Turtle-Dove, African Gray Hornbill, and White-browed Coucal. The summer breeding Gray-headed Kingfisher and Bruce's Green-Pigeon had gone with only the former turning up in the lowlands of Jazan.

Ultimately, it was only at the very end of the escarpment road that we found the final endemic—Arabian Sunbird. We had a female initially, followed by two stunning males during a walk along the wadi bottom. While suprisingly not as birdy here as previous visits, we did also find Arabian Black-crowned Tchagra, Blackstart, and Arabian Waxbill as well.

We paid a visit to Soudah Creek next, following up on a sighting of Levant Sparrowhawk by Rob Sheldon the previous day, a species that would be a life bird for both Jon and me. Virtually on arrival, Jon caught sight of an accipter with bright underparts but quickly lost it. We birded the area with an eye to the sky the entire time but, unfortunately, couldn't relocate what was likely the sparrowhawk. In the meantime, though, there was very nice birding in the wooded wadi here with lots of the more common endemics, like Yemen Thrush and Yemen Linnet, and our first Cinnamon-breasted Buntings among a loose feeding flock of House Sparrow, Ruppell's Weaver, Olive-rumped Serin, Yemen Linnet, and Ortolan Bunting. We eventually found one of the resident African Stonechat, a freshly plumaged male, easily mistaken for Siberian were it not for the habitat and very subtle plumage differences, like its large-headed appearance, the marked edges of its plain rump, and short primary projection.

A brief stop at Ayn Al Dheebah produced good views of a female African Stonechat, more closely resembling a European female on account of its darker, less contrasting throat among other similarities. Again habitat, large-headed appearance, and short primary projection as well as time of year would rule out either of the two migratory and wintering Saxicola species.

With time before lunch, we kept up our birding effort with a fairly unproductive stop at Wadi Reema followed by Dhaboo'y Dam. Wadi Reema is much better from May until September. Nonetheless, we had a few nice birds here with Whinchat and African Silverbill new to the list. The dam wasn't terribly birdy either with virtually no passerines detected in the trees around the north side of the reservoir. There was, however, a sizeable population of Red-knobbed Coot though, with over two dozen birds, mostly chicks and immatures with perhaps a half a dozen adults. This African waterbird's population has seemingly exploded in Saudi's southwest highlands. The first record came in December 2020. Since then there have been 75 eBird observations from Al Bahah down to the Jazan Region with some observers reporting numbers of well over 100 birds. This is perhaps one of the most rapid natural colonizations of a bird species on the Arabian Peninsula.

Having cleaned up on the Arabian endemics in just three days, we rewarded ourselves with extra down time to catch up on personal correspondences as well as some desperately needed sleep—all three of us were still dealing with persistent jetlag. Besides, we missed a chance for Little Owl in Al Namas and I was determined to add that to our trip list, so we'd have very early start the next morning to allow for an owl detour.

Day 5—Habala and Jebel Al Aswad

On our way to Habala, we stopped at a place I'd pinpointed in Google Maps the night before as promising Athene noctua habitat. We arrived 30 minutes before sunrise and sure enough just as the sun broke the horizon we had a pair responding to playback. While heavy traffic noise interfered with my recordings, the calls the male from this pair was giving were higher pitched yelps than given by the nominate subspecies in central and eastern Europe. The presumed subspecies here is A. n. saharae rather than the "Lilith" subspecies, which is more often reported from the east. The range limits and differences between the various subspecies in the wider region are ill defined, but one thing is clear—the Asir highlands host good numbers of this lovely little owl.

On the plateau at Habala, we found Rufous-capped Lark fairly quickly. Getting good views was another thing. We had several flybys and larks rising up ahead of us as we stalked closer, but they were quite energized that morning and loath to settle in any one spot. Eventually, though, our patience paid off when one calling bird flew up from behind a tussock and alighted on a rock a short distance from Jon and me. He remained there for a time, allowing great views of this tricky near-endemic.

We also had a nice close encounter with Isabelline Wheatear here. Just a funny aside about the dingy yellow-white color by that name, which the wheatear sports on its ear patches, neck, and breast. A previous client had told me it originated from an episode in the life of Isabella Clarra Eugenia, the Archduchess of Austria. When her husband, the Archduke, laid seige to the city of Ostend, Belgium, she swore not to change or wash her underwear until he had taken the city. Well, imagine now the state of her knickers when the seige finally ended three years later! The look of most of my childhood tighty whities, usually not so tight nor so white by the time my mom binned them, springs to my mind. Turns out, however, this squalid tale might just be a dirty joke from Victorian-era England, or so says The Secret Lives of Color by Kassia St. Clair, the relevant excerpt from which Charles emailed me recently.

We then birded a wadi thick with acacias in the hopes of turning up more of Jon's migrant targets. Indeed, we did find a good number of migrants, particularly at a temporary drinking spot created by the previous night's storm. While we watched a pair of Long-billed Pipits in for a drink, an Isabelline Shrike—there's that color again—followed by a Eurasian Wryneck, flew into a nearby bush. The shrike was a target along with Red-tailed Shrike, but October proved a little late for the latter. Isabelline had just begun to arrive and will spend the winter throughout the country. There were other migrants and early winter residents about, like Common Redstart and several Lesser Whitethroat (ssp. halimodendri). We also had nice, close views of a male Arabian Wheatear as well, noting those ID features for separating this resident endemic from wintering Mourning Wheatear.

Our time in the Asir Highlands had come to an end and we were on our way to the Jazan Region where we'd spend the night on Jebel Al Aswad, one of my favorite places in my favorite region of Saudi Arabia. Before taking off, though, we made a quick stop at the cliffs in Habala, and good thing too. While cruising slowly near the cliff's edge, I saw a group of raptors circling just over the precipice. In my bins, one jumped out as an accipiter with bright underwings contrasting with dark primary tips and richly marked underparts—Levant Sparrowhawk! Jon and I both subsequently got views enough of this mutual target to feel confident about the ID.

We made good time to Al Reeth, where we then climbed in elevation to reach our hotel on a dazzling ridgeline at 2000 meters, just as a cloudbank built up and began strafing across the ridge. After lunch of chicken with rice and a bowl of areekah, a calorie-rich savory-sweet dessert made with ground bread, cream, and honey among other very wholesome ingredients, we rested until an hour and a half before sunset and then set back out for late afternoon birding. On our way back down the mountain, we saw a half dozen Red-eyed Doves perched on powerlines beside the road. Any "collared" dove at elevation in the mountains of Jazan is more than likely this species.

We then snaked our way up another mountain road towards a stunning canyon where we would try for Desert Owl. On the way up we saw a column of raptors made up of both Steppe Eagles and Steppe Buzzards. At the end of the track, we waited for sunset, watching Eurasian Kestrels and Fan-tailed Raven working the updrafts along the cliff's edge above us, Arabian Partridge and White-browed Coucal calling from a scrubby slope nearby.

Just past sunset we stopped below a sheer cliff on our side of the canyon and tried for Desert Owl. To everyone's delight we immediately had two birds responding high above us. A short time later, two more Desert and an Arabian Scops began calling as well. We struggled to pin down the location of the two Desert Owls closest two us but eventually we did get one of the birds spotlit, its eyes glowing green and red, and Jon and Charles caught glimpses as it changed perches. Not the greatest of views but a sound tick nonetheless!

While we were scanning for the owls, we also had a flyby Montane Nightjar. This was at around 1500 meters ASL, the elevation at which these nightjars are known to winter.

As we headed back to the hotel, we were thrilled at our good fortune, particularly having seen five owl species up to that point, the best I'd ever done on tour.

Day 6—Abu Arish

The plan for the morning was to drive to the village of Gamri early to ensure we had enough time to look for Arabian Golden Sparrow. On the way, we had an adult Oriental Honey Buzzard quite close to the road as well as a flyby Gabar Goshawk. At Gamri, however, there was no sign of the sparrows, so we continued on to the village of Fels. Here too we had no luck, so headed into Abu Arish to check in to our next hotel. Once in town, we made a quick stop at the cemetery where I first saw golden sparrow back in July 2020. There were no sparrows this time, but we did see our first Gray-headed Kingfisher of the trip, presumably an over-wintering bird given how abundant this species is from the mid-elevations up during the spring and summer and we hadn't seen any up to that point.

After pizza and some down time at the hotel, we headed to Al Sadd Lake for some night birding. We got there less than an hour before sunset, enough time to try for migrants in the acacia, mesquite, and tamarisk along the southern edge of the lake. Besides Spotted Flycatcher, there weren't any other migrants, but our trip list got a significant boost from the many shorebirds and waders in this area, including a flyby Hamerkop. African Collared-Dove was new here for Jon. African Palm Swift and Zitting Cisticola flitted overhead.

After dark, however, the birds we were really hoping to see became active. Following their calls led to our first views of Nubian Nightjar, which we'd see a few more of by the time we left. Searching an open area ringed by tamarisk that I thought would be good for Egyptian Nightjar actually turned up two Plain Nightjar, yet another of Jon's targets, and not one I was anticipating at this site.

Besides the nightjars, also of interest here were vocalizing Helmeted Guineafowl. These birds, unfortunately, were in the direction of the road, so I couldn't get as good a recording as I had hoped, but pleased nonetheless at an audio tick for Saudi.

Day 7—Abu Arish, Jazan, and Sabya

The next morning, bright and early, we were back out in Gamri looking for golden sparrows. This time we had luck, first seeing a distant flock of about 15 birds in an acacia midfield and then later, beside a neighborhood, lovely views of several Arabian Golden Sparrows foraging with House Sparrows and Ruppell's Weavers.

On our way back out to Al Sadd Lake, we stumbled upon a large flock of pratincole feeding on an insect bloom, about ten percent of which were Black-winged, one of our shorebird targets.

Back out at the lake it was already starting to get hot. Besides Eurasian Spoonbill and our first and only Singing Bushlark, we didn't see much more than we had the previous afternoon, so after breakfast we decided to check out of our hotel and head to Jazan, where Rob Sheldon reported a large gathering of Abdim's Stork.

On arrival to the Jazan Heritage Village, we couldn't miss the storks, with the majority of the 46 birds present perched atop light poles throughout the area. These had to be one of the easiest ticks of the whole tour. This Afrotropical species is a resident breeder, building its nests on telecommunication towers and other tall pylons, but during the winter its numbers are augmented by an influx of birds from Yemen and possibly the Horn of Africa.

This spot was also great for waders and shorebirds with several new additions to the trip list, like Pied Avocet, Tibetan Sand-Plover, Bar-tailed Godwit, and Western Reef-Heron among others. Here we also had our first White-cheeked and Saunders's Tern, the latter IDed with care as they are difficult to separate from Little Tern in non-breeding plumage. The coastal birding actually proved quite productive on this visit with several more good finds to come.

Before heading to our next spot, we checked out a nice mangrove forest nearby. Both white and dark phase WRHs were present, and Charles and Jon had a flyby Collared Kingfisher. Jon and I also saw a few of the mangrove subspecies of Common Reed Warbler (ssp. avicenniae).

Next we visited the wastewater treatment plant. There had been significant rainfall in the area with many areas still inundated and overflowing with accummulated rainwater from that storm and surely several previous as we were at the tail end of the monsoon season here. With this heavy injection of freshwater into the mangroves here via the wastewater system, I wondered if Lesser Flamingo would be back. During a period when the plant dialed down their ouput, the large flocks of flamingo all but disappeared from the mudflats. My suspicion was correct. While not the few hundred seen in the past, there were at least 100 flamingoes with around a third Lesser Flamingo. This is the only place in the Kingdom where this species is known to regularly occur.

At my go-to site for seabirds in the south corniche area, we found a large number of gulls, terns, and shorebirds with Sooty Gull crossed off the target list. Just offshore on a rocky strip, we found our first Goliath Heron, the first I'd seen on the mainland of Jazan.

We then made our way into the city of Jizan proper. A quick stop at the fish market netted us over 35 White-eyed Gulls, by far the most abundant gull around this port city.

After lunch I sorted out our tickets for the ferry crossing to the Farasan Islands the next morning and then we checked in to our hotel. The plan was to relax until late afternoon and then head to Sabya to try for Hypocolius before sunset.

We got to the cluster of fields and plantations where we saw hypos coming to roost in March 2022 just as the sun was dropping out of sight behind the nearby village. We quickly made a pass of the hypo roost from previous years and then other noisy, active roost trees in the area but no hypos were detected. I suspected it was still early for this striking monotypic.

The drive to Sabya wasn't a complete loss though. I'd say we were more than compensated with Jon's third nightjar lifer from two consecutive evenings of night birding. Just after dark we found four Egyptian Nightjar along with a couple Nubian hunting out over the open fields. All in all we did incredibly well with nocturnal birds, recording five owl species and four nightjars during the week. Jon and Charles were well pleased.

Day 8—Farasan Islands and Sunbah

Our crossing to the Farasans the next morning produced many of the common species, like Brown Booby and Lesser Crested Tern, but none of the rarer birds I had been hoping for. Our boat tour with Abu Ibrahim, on the other hand, was quite successful, making the overall effort totally worth it.

We first visited the Al Qandal mangrove forest, needing to get there while the tide was still high so we could venture deep inside the lagoon and ensure that we could make it back out without running aground. On the way in, we saw Egyptian Vultures and the first of several Osprey. Back among the trees, we soon discovered that Pink-backed Pelican had indeed begun nesting. It was nice seeing them in full breeding condition, particularly the large dusty-rose patch on their lower back and rump, from which they get their common name.

Turns out there was another pelican species present, with this lone Great White Pelican showing off peak condition as well.

The encounter here that left us the most gobsmacked was coming upon a pair of nesting Goliath Heron. I had never been so close to such an impressive bird, Goliath representing the world's largest heron, its wingspan 220 cm (7.2 feet) to the Great Blue Heron's 175 cm (5.7 feet). Abu Ibrahim, our expert boat captian, knew not to drift too close and knew just when to cut the engines to minimize our disturbance and enhance the moment, leaving just the sounds of the water against the hull and our own hushed expressions of amazement.

At one point, one of the pair, the female I suspect, flew out of the nest and stood in the shallows along with her mate, at which point the male issued a series of grunts. The female then gave a whoop-WHOOP-whoop in reply. I isolated these vocalizations to be uploaded separately to the Macaulay Library and Xeno-Canto and was surprised to find how few recordings of this species there actually are. While there are almost 4000 images of Goliath Heron in the Macaulay Library, the isolated audio clip below is one of only three. Wish I had had my recorder going as well!

From there, we called in at a seabird roost, enjoying close views of adult White-eyed Gulls as well as White-cheeked, Lesser Crested, and Great Crested Terns, before heading out for the prime target of the morning—Sooty Falcon.

There's a small island chain northeast of the ferry terminal that birders have been visiting since I first pinpointed the spot in Google Maps for Abu Ibrahim back in May 2021. He had never taken tourists out to this spot before, the typical tour only stopping at the mangroves and then veering out to sea at speed long enough to attract a pod of Spinner Dolphins. Since our first visit, he has taken several groups of birders out to see the falcons, most of whom I've steered his way through my remote guiding service. He spoke of this appreciatively during our recent excursion, and I, in turn, appreciated how skilled he has become at bird spotting and catering to the specific needs of birders and bird photographers. Jon and Charles complimented him on the overall experience as well.

On this visit to the islands, we stopped at three of the most promising—higher with sheerer edges—and found six adult Sooty Falcons. Surprisingly, there were no immatures, suggesting perhaps that they had already dispersed now that the flow of migrant passerines crossing to Africa was winding down. Soon they too would head south to their wintering grounds in East Africa and Madagascar, returning in late March just in time for the springtime return of Western Palearctic migants.

It was hot out there on the water, particularly when the boat was at rest, so I was grateful that Jon and Charles permitted me to swim a little before heading back to port. It had been over two years since I'd last swam in the Red Sea, so I was aching to jump in and soak my travel-weary bones!

So we actually returned to the marina in time to catch an earlier ferry, which allowed us to get in some late afternoon birding around Sunbah. There were a few remaining targets I expected we had good chances of finding there if the conditions were right, one of which was Caspian Plover, which we had seen a large number of at Sunbah in October of last year. Those birds, however, were on a recently tilled field, mostly bare dirt with only a skim of green where sprouts were emerging. When we got to Sunbah, we discovered that nearly all the fields were in later stages of cultivation, some with meter-high growth—not conducive for plovers and Sociable Lapwing, the other steppeland target we were hoping for here. We did find a couple of fields being watered with lower growth but no shorebirds were found. There were, however, Steppe Buzzards, Western Cattle Egrets, Blue-cheeked Bee-eaters, hordes of Yellow Wagtails, a few Northern and Isabelline Wheatears, and one striking Richard's Pipit, my first for Saudi. We did find one of Jon's targets—Black-crowned Sparrow-Lark—with several bold males showing well. There were also a few other interesting birds of prey as well. On one field we found an adult and immature Montagu's Harriers and further on a male Western Marsh Harrier. Interestingly, we also found two subspecies of Black-winged Kite, the nominate (ssp. caeruleus), which ranges across Africa and into southwest Arabia, as well as the Asian form (ssp. vociferus), which has spread rapidly across the Arabian Peninsula from the east. The latter can be told from the former by dark secondaries on the underwing.

Day 9—Sunbah and Jazan

The next morning, the start of our final day, we went back out to Sunbah to revisit the most promising fields. There were still targets to be had, especially since a few were odd ones to have missed up to that point, like Upcher's Warbler and Pied Wheatear. Yet, despite a thorough thrash of fields, scrub, and acacia stands around Sunbah, our luck had run out targetwise. That said, we did succeed at some expert level list padding, going from 185 at the start of the morning to 197 by the time we called it. At Sunbah, we added Pied Cuckoo, Common Cuckoo, and Abyssinian Roller. While not new for the trip, we got great views of Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse here as well—always welcome! We were particularly mindful of shorebirds missing from our list, enumerating them as they came to mind on our way to some of the best shorebird spots in Jazan. Remarkably, we did indeed locate several of even the less predictable ones. At our first stop along the North Corniche, we found Greater Sand-Plover and Broad-billed Sandpiper. At our next stop, Northern Shoveler—the birding gods must've heard Jon comment on how we had no ducks and so tossed some dabblers in the Red Sea. Sure, why not!—Eurasian Oystercatcher, and Slender-billed Gull. Back at the heritage village, Terek Sandpiper, Ruddy Turnstone, and Tree Pipit. Then, final bird of the tour—Spur-winged Plover at the wastewater treatment plant.

Though I knew it would add to an already busy six months, what with three other tours planned from next month until May, when Jon contacted me about helping him put together a bird tour during his visit, I couldn't honestly say no. Sure glad I didn't. Charles and Jon are really interesting guys—as you might imagine—and were a pleasure to go birding with. I hope that with my help they had an even more memorable time in Saudi.

Interested in going birding with Saudi Birding? Click HERE to explore expert-guided bird tours in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere around the Middle East. We also offer custom tours, combining targeted birding with other experiences tailored to your personal interests and preferences.